The Redemption of Pritchards Island

story by ERIN WALLACE

photos by TESS MALIJENOVSKY

and courtesy of USCB

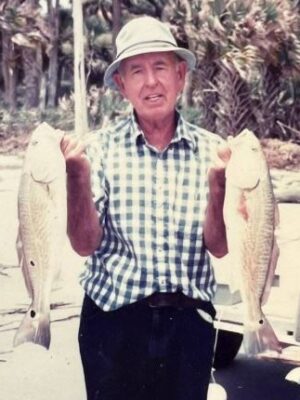

You know the saying, “Give a man a fish, and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” Well, there was a legend of a man who took the meaning of this well-known quote to the next level! Not only did he love fishing, he owned an island that he enjoyed as any fisherman would. His name was Philip Rhodes, and this island was named Pritchards Island, an island off the coast of our town that happens to be one of hundreds of barrier islands dispersed throughout the vast southeastern coast.

However, it is not just any old island; it is a flourishing 1,600-acre expanse with all kinds of wildlife to boot. Thus, it was Philip Rhodes’ “happy place,” says one of his sons, Steve. Generously enough, though, Philip intentionally shared his island with friends and family. He would eventually gift it to the University of South Carolina Beaufort (USCB). This was a man who didn’t want to keep the fish to himself, and certainly fed our community and beyond in the same breath.

Who exactly was Philip Rhodes? To start, he was a very successful man, not originally from Beaufort, but a Southerner, nonetheless, being born in Atlanta, Georgia. Philips attended Emory University, and then the University of Georgia, where he graduated in 1938 with a B.S. in Business Administration. After college, Philip would go on to serve as a quartermaster in the United States Marine Corps in the South Pacific and the Philippines. In 1941, he met his wife, Edith Goodman. He married Edith at 25 years old; at that time, they could only afford a garage apartment on his wages as a brand new manager at S.P. Richards Paper Company in Montgomery, Alabama. Over time, with Philip’s intentional leadership, S.P. Richards received national growth and acclaim. Therefore, he continued as its president, being the hardworking man he was, until his retirement in 1984.

photo courtesy of Steve Rhodes

Philip accomplished far more in a lifetime than you could imagine was humanly possible. Alas, he passed away in 2009 and is survived by his sons, Alec and Steve; his grandchildren, David, Martha, Caitlin, and Nathan; his great-grandchildren, Josh, Jake, and Jesse; and his great-great-grandson, Landon. There is no doubt that Philip’s giving nature was apparent in his everyday living through grit and commitment, such as being a lifelong supporter of many local organizations, like the Boy Scouts, the Boys and Girls Club of America, and many more. His obituary reads, “Phil Rhodes will be remembered as an extremely generous and modest man who did what he saw as right with little fanfare.” A humble man at best, he will never be forgotten, and his memory lives on in many ways. With Pritchards Island on the map (specifically ours), the Lowcountry will forever be indebted to this selfless fisherman and his generous contributions.

Continuing, how did Philip find this island in the first place? Great question! This specific island had been displayed on Beaufort County’s auction block because Pritchards had been seized from its former owner Georgia Sen. Eugene Holley in a lawsuit due to unpaid mortgages. It would turn out that Holley had big plans for the island before then, proposing to fill the barrier island with housing developments. However, there was one huge plot twist when Philip outbid media mogul Ted Turner and purchased Pritchards for $1.275 million in 1979. The plans for the houses were erased when the deed was in Philip’s hands! Holley’s loss was Philip’s gain, as his main vision for the property was to conserve his island.

In other words, he wanted to utilize the barrier island to educate the public and allow research scientists the opportunity to better comprehend barrier islands without the fear of encroaching vast development on the horizon. Inevitably, Rhodes decided to give his uninhabited island to the University of South Carolina for future preservation and research. Pritchards Island’s vision statement is “Amid burgeoning growth and tourism, a pristine barrier island offers the profound opportunity to conserve, educate, and cherish our imperiled Sea Islands, which hold significant ecological, cultural, and economic value to the Lowcountry and have defined the coastal southeast for millennia.” What a beautiful vision that wouldn’t have been possible without Philip’s best interest in mind for the island. On top of gifting the island to USCB, he also fully funded the construction of a stilted lab building. But it didn’t end there; Philip made generous financial contributions to aid USCB and keep Pritchards operations on their feet.

In other words, he wanted to utilize the barrier island to educate the public and allow research scientists the opportunity to better comprehend barrier islands without the fear of encroaching vast development on the horizon. Inevitably, Rhodes decided to give his uninhabited island to the University of South Carolina for future preservation and research. Pritchards Island’s vision statement is “Amid burgeoning growth and tourism, a pristine barrier island offers the profound opportunity to conserve, educate, and cherish our imperiled Sea Islands, which hold significant ecological, cultural, and economic value to the Lowcountry and have defined the coastal southeast for millennia.” What a beautiful vision that wouldn’t have been possible without Philip’s best interest in mind for the island. On top of gifting the island to USCB, he also fully funded the construction of a stilted lab building. But it didn’t end there; Philip made generous financial contributions to aid USCB and keep Pritchards operations on their feet.

Sadly, Pritchards Island isn’t what it once was since Philip’s death 14 years ago. With erosion eating hundreds of yards of island dunes, as well as dried up funding in the mix, the island has been sadly unused by USCB for over a decade. So, the lab building that was once one with the live oaks and palmetto trees is gone. It may be true that Philip’s physical traces are fading from the island, yet his legacy is even louder than ever as the Rhodes family is fighting for the redemption of Pritchards Island. This is represented through USCB recently being granted money through the state to get research projects going. From the ashes of what Pritchards Island once was, rises a phoenix of hope for what is yet to come.

photo by SUSAN DELOACH

Dr. Kimberly Ritchie, director of Pritchards Island Research Program, says, “When I stepped on Pritchards Island for the first time, I felt a sense of wonder and excitement. It’s like stepping back in time.” These feelings are attributed to the fact that Pritchards is not a nourished beach but a natural one. Due to its preserved nature, you can witness formations on the island that wouldn’t be seen on a developed island, such as black coral-like formations that appear to be petrified pluff mud and a breathtaking boneyard beach that spans for miles. The resources on the island are ideal for building a marine science program with projects that incorporate continued monitoring of sea turtle nesting; surveys of horseshoe crabs, shore birds, migrating birds, and reptiles; and the island’s botany, geology, and much more. Kim’s next goal is to figure out how to get students on and off the island for extended studies because once this dream becomes reality, the possibilities are limitless. Redeeming the sacred space of Pritchards started over forty years ago when a fisherman caught a fish of a lifetime. There is much to be learned about the baseline ecology of Pritchards and the water surrounding it. It’s a good thing the fish (Pritchards) belong to Beaufort, and now USCB has the opportunity to continue the work they started that Philip Rhodes desired for his island. If you ask me, I believe it’s in good hands.