ROBERT MIDDLETON

A Life and Legacy Built On Love and Culture

story by JENNIFER BROWN-CARPENTER photos by JOHN WOLLWERTH

Beaufort is full of history, from the church ruins at Old Sheldon to the homes built during the 1800s that stand under oak trees downtown to Fort Fremont. One thing that almost all of these things have in common is informational signs, plaques, pamphlets, and sometimes even tour guides.

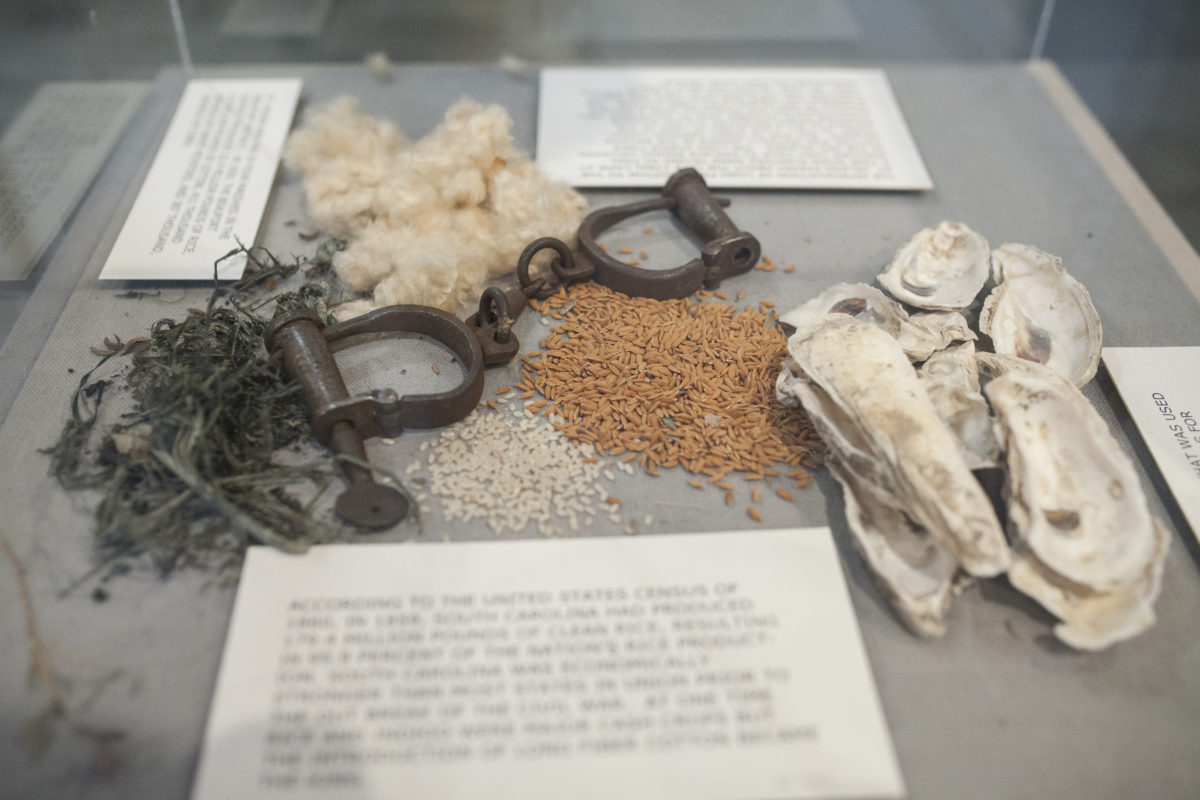

Penn Center is one such historic location. It was the very first school opened for recently freed slaves in 1862. You can tour the York W. Bailey Museum at Penn Center and walk the grounds. There is plenty of informational signs and plaques, but the difference between this location and all the other historic locations in Beaufort County is that your tour guide, Robert Middleton, grew up on St. Helena Island and attended Penn Center himself as a child.

Robert Middleton is one of those men who never meets a stranger. At 90 years old and standing at 6’2″, his cheerful grin puts you immediately at ease. While his story is marked by confusion and hardship, it is not one that has made him bitter or hardened against the world. Instead, Robert is joyful and full of love. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Robert was adopted by James and Elizabeth Middleton as a baby. James owned a farm on St. Helena, where he raised turkeys, hogs, cows, chickens, horses, you name it. They also grew vegetables, watermelon, cotton, rice, sweet potatoes, and okra. It was on this farm that Robert was raised in the Gullah culture.

Gullah, also known as the Sea Island Creole English and Geechee, is not just a culture. It is traditions, customs, and beliefs that have been passed down generation to generation. The language, a mixture of African dialect and English words, created by slaves, as well as the land, food, arts, and music, is a symbol of history and pride. These traditions are the Foundation for the Africans who were forced to adapt to the new land they found themselves in. It is a Foundation that has built up a community of love and service.

“Everybody helped everybody else.” There weren’t many cars on the island back in the early 1930s, and everyone would walk and talk and mingle with their friends and family members. They would share stories, food, and church services. They would share remedies when someone was sick, including using a frog to draw out snake venom, and there was a midwife who would deliver the babies.

The islanders would attend church on Sunday and go to “praise houses” on Tuesday, Thursday, and Sunday nights. The praise houses were a tradition passed down from the plantation system when large amounts of slaves would gather to worship without leaving their owner’s land. You can still see some of these praise houses on St. Helena today.

Growing up during the Great Depression brought hardship. Robert had to work alongside his father to help buy food and necessities. He helped by selling fish house-to-house in his neighborhood, either walking or in an ox-driven wagon. James taught Robert how to cast nets, pick oysters, fish, and crab.

Robert began his education at the Lee Rosenwald School on Seaside Road. After he graduated from primary school, he started attending Penn Normal and Industrial School. At the time, it was the only school near enough for the children on the island to attend. It also served as a boarding school for children from Savannah, Hilton Head Island, and the Bluffton area. Most of the children in school grew up on farmland and they would each have time off school in the fall to help with the harvest. Unfortunately, to graduate, you had to spend your full last year on campus, and because James needed Robert’s help on the farm, he left after completing the 11th grade.

In January 1951, at age 22, Robert was drafted into the United States Army. He went on to serve as an engineer in Germany during the Korean War. After his stint in the service ended, he came back to St. Helena and worked at Parris Island in the Officers Club for several years.

James and Elizabeth Middleton had never talked to Robert about his adoption, and most of what he had heard about it came from outsiders. There was gossip that went around about his birth mother and even some people who said Robert was Puerto Rican, because he looked different than most of the people living on St. Helena at the time. Robert didn’t really understand what all this meant when he was a child, and so he never asked any questions. He knew that his parents loved him and prayed for him, and that was enough as a child.

But at the age of 29, Robert moved to the city of brotherly love, looking for answers. For two years, he lived and worked in Philadelphia. After that, he reached out to a local newspaper, The Philadelphia Tribune, asking for help finding his parents. He provided a picture of himself, and shared his date of birth and that he was adopted.

He did find his parents. They lived just a few blocks from where he had been living, and he had passed their home multiple times while walking to work. John “Cup” Ford, Robert’s biological father, was a bartender at a local bar that Robert had visited, but the two had never run into each other. Robert also met his mother, his grandmother, aunts, and five siblings. He found out that his great-grandmother had worked in the White House during Woodrow Wilson’s presidency and that he had a great-grand uncle who was a Justice of the Peace. Having relatives who had worked in such notorious positions was something that Robert was very proud of. It was a family treasure to pass down to his children and grandchildren.

Robert formed a close bond with his biological parents. It was as if they had never been apart. He spent time every day with his father for the next 11 years until “Cup” passed away in 1969. Marian and Robert had 18 years together before she passed away in 1976. Robert was able to learn about why his parents gave him up for adoption, “God had His plan, and God’s plan never fails.” Marian knew the Middleton family was loved and respected, and she trusted them to raise her son when circumstances prevented her from doing so.

Robert stayed in Philadelphia until he felt that it was time to return home. In 1976, when both sets of his parents had passed away, he came back to St. Helena and settled down on the farmland that he grew up on. He still lives there to this day. Robert raised seven children, six of whom still live in the area. They all graduated high school, and have jobs and children of their own. He has 23 grandchildren and more than 27 great-grandchildren.

He started volunteering at Penn Center in 1999 and will continue as long as he’s able. He is there five days a week, ready and willing to be a personal tour guide or to share his life story. He loves having the opportunity to share about the natives of St. Helena Island and the other important historic sites on the island. He has been a deacon at First African Baptist Church on St. Helena for 37 years.

When asked about the differences between the two families, biological and adoptive, Robert says: “Both sides of my family were beautiful. I want the world to know that I am a very, very lucky person. My father, James Middleton, used to say, ‘it’s not what you got, but how you use what you have. If you have a roof over your head, clothes on your back, food in your stomach, and Christ in your life, you’ve got everything.'”

Robert’s motto in life is simple: “the key to everything is love.” This motto is evident in the way he greets you as you walk toward him. It’s evident in the way he shares his story. But Robert doesn’t credit this joy and love to himself, or either set of his parents. “I want to thank God. I tell you this story because God was good to me. And God is good to you. Don’t think about where you are going, but where you came from. He will lead your path to where you want to go. Just trust in Him and believe in Him.”