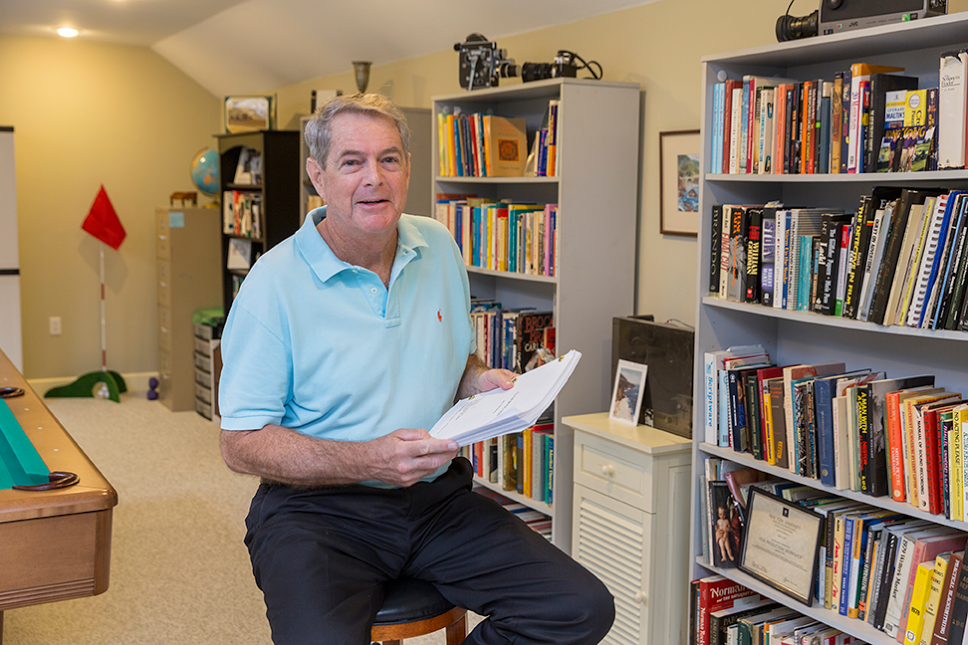

Tom Bixby: Losing His Reality and Finding Himself

story by carol lauvry photography by paul nurnberg

If you attended the 9th Annual Beaufort International Film Festival’s awards ceremony at USCB’s Performing Arts Center last February, you were treated to a lavish cocktail party and an exciting, star-studded evening of film awards presentations. The award for Best Screenplay that evening was presented to Saint Helena Island’s own Tom Bixby for Club Bong Son, a screenplay recounting the emotional Vietnam War experiences of a fictional 19-year-old military policeman.

Most people at the awards ceremony would not have guessed from Bixby’s humorous and upbeat acceptance speech, that the screenplay draws heavily on memories of his own time spent in Vietnam—memories that still haunt him. If you were not on hand for the screenwriters workshop and the reading from Club Bong Son, you did not experience the gut-wrenching mental images conjured by Bixby’s jarring words, describing the unimaginable horrors of the war.

Tom Bixby, who directed, wrote and produced films for more than 35 years, says his screenplay is about “what you bring home with you from the Vietnam War and what gets lost inside.” He wrote Club Bong Son during the 1980s when he first began to understand the toll that Vietnam had taken on him.

Losing Reality

Do they still dream

The men I killed

As I still dream of them

Can they see

My eyes at night

The way I still see theirs…

They do still scream

The men I killed

And I still dream of them

They can never

Go back home

But neither can I

(Excerpts from the poem, Do They Still Dream, copyright 2009 by Tom Bixby)

Bixby says he began to lose his reality after returning from a 1967 – 1968 tour in Vietnam, where he served as a military policeman in a field detachment of the 272nd MP Company, “the Fighting Deuce,” and as a helicopter door gunner with the 201st Aviation Company. He started college when he got back from the war, but had an emotional breakdown in 1970 at the age of just 22, citing the anger and grief he had suppressed from events in his childhood and the Vietnam War as the cause. During his three-year struggle to overcome his breakdown, Bixby learned to achieve a kind of meditative state while painting and drawing as he watched old movies. This helped his repressed emotions of anger, then deep grief, and finally joy, surface. “It was a long process, but at the end of it I was able to feel joy and freedom that was unknown to me during my disease or even before I fell ill,” he says.

During the years following his breakdown, Bixby says he was a highly functioning individual, pointing to his extensive accomplishments (see the related sidebar article). He had no idea of the far-reaching effects that the war still had on him until after September 11, 2001, when US troops including his own son went back to war. His memories of Vietnam began to resurface in a dramatic and devastating way and he learned that other Vietnam Vets, including buddies from his own unit, who were widely known as the “Bong Son Rangers,” shared his ongoing torment.

As Bixby recounted a surprise phone call he received in 2001 from his military policeman buddy ‘Vee,’ his brow furrowed and his eyes teared up. Vee wanted Bixby to call their friend ‘Shu’ who was fighting demons from his time in Vietnam. Bix (Bixby’s nickname in Vietnam) and Shu hadn’t spoken in years, but they talked on the phone for four hours about struggles with war memories and symptoms—the inability to sleep, hyper-vigilance, exaggerated startle response to noises, flashbacks and more. Bixby met with Shu in Arkansas for an “all you care to eat catfish lunch.” The man who sat across the table from him did not look the same as his friend in Vietnam—since then Shu had grown several inches taller and was a bulkier man—but Shu had the same voice Bix had heard beside him in the bunker as they fought the Viet Cong. Bixby said the emotion of recalling incidents from their time together in Vietnam unleashed long-dormant memories for him.

Talking with Shu, Bixby realized he had been suffering from the same Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms and that they had become more extreme after September 11th. In 2002 the Veterans Administration certified him as permanently and totally disabled due to PTSD. He recounted an incident when he was filming a piece in Cooperstown, NY in the back yard of one of the town’s patrons of the arts. “Someone in the next yard fired a shot to kill a varmint. I immediately hit the ground, pulled the camera over on top of me, and tried to shoot back with the camera,” he exclaimed.

In an essay he wrote in 2010, Bixby relates another disturbing incident that happened when he was out with his young children, daughter Kayla and son Morgan. “Something falls off a shelf at Toys-R-US. It makes a loud bang. Your muscles contract. You let out a small yell. You dive into a crouch and your hands fly up into a firing position as if you had a rifle. Your head whips toward the noise. Your kids freeze. ‘Whoa,’ says your eight-year-old daughter as she stares wide eyed and open mouthed at the monster that just leapt out of the closet ready to kill.” (Excerpt from, A Case of the A.S.S., copyright 2010 by Tom Bixby.)

In 2012, Tom Bixby’s worst nightmare came true—his 22-year-old Army Ranger son, Morgan, who had completed three tours of duty in Afghanistan, committed suicide. Morgan suffered from an extreme case of PTSD due to life-altering experiences while he was deployed. His Army Ranger unit had to break off a successful assault and instead fight their way through an imminent ambush to protect the crash site of the downed Chinook helicopter, carrying members of Navy Seal Team Six. Morgan had to spend 48 hours on that site with the burned and co-mingled bodies of the Seal Team members—men who had comprised the other half of his strike force and who had tented with and worked with Morgan for months. In separate incidents during the same deployment, his mentor and best friend was mortally wounded and died in Morgan’s arms, a junior member of the fire team Morgan led was killed, and more than a dozen members of his platoon were wounded.

After he returned home from Afghanistan, Morgan married in 2012. Just a few months later, though, when Tom and his wife Patti were in route from California to move to Beaufort, they received the call telling them Morgan had died. PTSD has devastated two generations of the Bixby family.

Finding Himself

Tom Bixby has just written a new book scheduled to be available by February 2016, Crazy Me—How I Lost Reality and Found Myself, published by MPM of Stockbridge, MA. (For more information on his book, visit www.myserenitypress.com.) Crazy Me is a moving personal account of Bixby’s fight to recover from PTSD with Schizophrenia. Bixby says that the book reveals the “split mind” of the disease as a battle between a long hidden natural self and a false self, created to survive a world of childhood disease, bullying, emotional repression and the horrors of war.

“I entered therapy in the 1970s, and as incidents from my past surfaced, I had to look deeper and do more reflection,” Bixby said. “What I’ve discovered is that I had to stay with feelings. I feel that now, I’ve found a floor upon which I can rest and open space above me to explore.”

“For years I had resisted or denied my feelings to the point that I began to lose touch with external reality. I lived in constant terror that my body and the world around me would dissolve and my naked soul would fall for all eternity into an endless pit of black flames, pursued and tormented by demons. What I finally discovered was that even the most excruciating and disturbing of my repressed feelings wouldn’t kill me. The crazy world I had invented merely served the purpose of concealing the feelings I was so afraid of. When I was finally able to experience them fully and directly through my art and psychotherapy, I not only found my true self, but I discovered the world was a workable place after all,” Bixby explained.

Tom Bixby: Director, Producer, Screenwriter, Scholar, Veteran

Templar Films

Tom Bixby has directed, written and produced more than 1,000 commercials, sales, training and promotional films, and marketing campaigns over his career spanning more than 35 years. His clients have included Ford, Texas Instruments, KFC, Levi’s, IBM, Playtex, Suzuki, The New York Times, NAPA, DuPont and Upjohn, to name a few. Bixby’s work has garnered dozens of awards for his clients, including a National Telly for best retail spot and a number of first and second place awards from the International Association of Business Communicators, the International Television Association, the American Advertising Federation, and the Public Relations Society of America.

Education

He earned a BFA degree in Film Production from New York University, where he also served as a technical instructor. In addition, he completed graduate studies in psychology at UCLA and at Vanderbilt University.

Organizations

Bixby has been listed in Marquis’ Who’s Who in Entertainment. He is a life member of Disabled American Veterans and is a member of Vietnam Veterans of America, Directors Guild of America, Mensa and Triple Nine Society.